Drawversity what? Drawversity where?

They say necessity is the mother of invention. Drawversity was created from my own experience working as a life model – living in such a creative city where Life art is so popular – I had found there really weren’t enough BIPOC Life models in the industry, in a city where there were so many Life Drawing studios and artists. I wanted to change that, to try and eliminate the class and culture barriers of Life art and modelling. For our children and children’s children, to see a reflection of themselves through art in history and not as a monolith, where the protagonist has control of the narrative.

Due to the epidemic in 2020, I was faced with a barrier, so I teamed up with Draw Brighton to do an artist’s reference photoshoot for creatives who were signed up to their Patreon and drawing at home – this really helped create a buzz about the class with the Draw community, who became eager to attend once the studio was back open. Since March 2022, I have been running monthly classes at Draw Brighton, in 2023 I started running bi-monthly classes at SOHO Brighton Beach House, and since the start of 2024, I now host a monthly class in Hove at wellbeing studio, Fine Feather Wellness. Now five years running (minus lockdown years), the class has really developed; with more of a guided approach to the model, the artists are able to see how the life modelling side of the collaboration between artist and muse works, creating a more synergetic energy in the class.

Oh La-De-Dah you’re an artist, are you?

The industry of art as a luxury and privilege – particularly in relation to race – is tied to historical and socio-economic factors.

- Historical Context: Art has often been associated with wealth and privilege. Throughout history, access to education, resources, and networks necessary to create and promote art has been predominantly available to affluent white communities. This legacy continues to influence contemporary art markets and institutions.

- Systemic Inequalities: Racism and systemic inequalities have historically limited opportunities for many Black artists. Factors such as accessibility to education, funding, and exhibition spaces can disproportionately affect marginalised communities, making it harder for artists of colour to gain recognition or financial support.

- Cultural Appropriation and Influence: Many artistic styles and movements have been significantly influenced by Black culture. However, these influences are often co-opted by others who then profit from them without giving due credit or compensation to the original creators. This raises questions about the ownership of cultural expression and the dynamics of power within the art world.

- Art Market Dynamics: The commercialisation of art often favours artists who are able to market themselves effectively or have access to networks that open doors to galleries and collectors. This can exacerbate inequalities where established artists, often from privileged backgrounds, dominate the market.

- Changing Landscape: There is a growing movement advocating for diversity and representation in the art world. Some institutions and collectors are recognising the need to support Black artists and other marginalised creators, though systemic change takes time.

In summary, the intersection of race, privilege, and art reflects broader societal issues. Understanding and addressing these complexities is crucial for fostering a more equitable art world. Which brings me back to Drawversity and why it is so needed. All these points listed can make the Black Community unenthusiastic to enter into the creative world as a serious career path, from a young age, many of us are steered to more academic jobs that will land us in more stable financial positions, this then creates a whole lot of unknown paths of self-expression and creativity. Life Modelling wasn’t something I myself knew about, and I possibly wouldn’t have seriously considered it a job, had not someone from my own community recommended it as a way of working. That’s why it’s so important that we have the opportunity to create these spaces ourselves where we feel free to explore how we can be expressive with our physical self in such a vulnerable state.

Throwing Shapes.

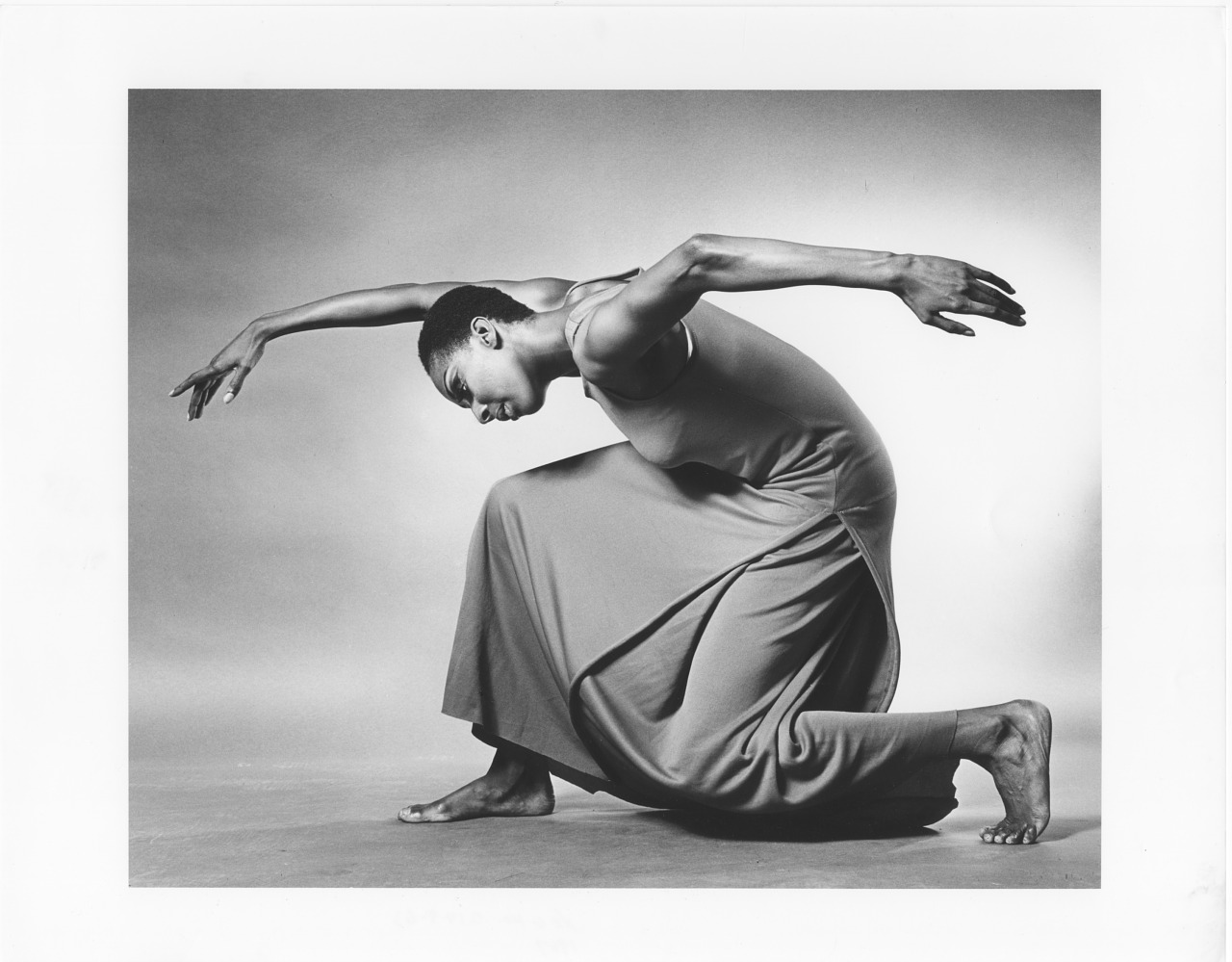

Life Modelling, often seen in art studios, involves posing for artists who are sketching, painting, or sculpting the human form. This practice allows models to create various shapes and forms using their bodies, showcasing the intricacies of human anatomy.

Participating in Life Modelling can provide a unique opportunity to disconnect from the outside world and connect with oneself. As a model, you often enter a state of mindfulness, focusing on your body’s position, balance, and breath. This intentional focus can be a meditative experience, allowing for a deeper awareness of your physical self and how it interacts with space.

While posing, models create dynamic shapes with their limbs, producing a visual language that inspires artists. Each pose contributes to the narrative of the artwork, infusing it with emotion and energy. The process of maintaining stillness and exploring different poses cultivates a sense of presence, helping models appreciate their body in a new light while also encouraging creativity in those observing and creating art.

In this way, life modelling is not just about holding still; it’s an artistic collaboration that bridges the gap between the model and the artist, offering both parties a moment to explore and express their creativity. Through this practice, models often find a sense of peace and self-connection that can be both rejuvenating and empowering.

[…]

I was on the phone to my mum, when she asked me about work, I told her how I wanted to do something special, something educational for Drawversity during Black History Month. I told her what I’d done the previous years and how I had researched and written up about Black Models and Muses, from Josephine Baker, to Aïcha Goblet and Jeanne Duval. As we spoke, we got onto to talking about the recent and tragic loss of Michaela DePrince, a beautiful ballet dancer headlined a ‘trailblazer’ who had recently been made a soloist. As the still images of her flying through the air, every muscle in her leg traceable, the beautifully crafted shapes, and the energy the movements emanated from the images, I started to go down a rabbit hole of contemporary dance and the influence Black culture had on it. I wanted to take a look at some of the most influential contemporary – Jazz & Ballet – Black dancers, and how they have shaped dance and movement.

Michaela DePrince

“Michaela DePrince was born in war-torn Sierra Leone, right in the midst of the country’s decade-long civil war. Rebels killed her father, and shortly after, her mother died of fever and starvation. At a young age, Michaela had vitiligo, a condition that causes patches of skin to lose its colour. In Michaela’s motherland, vitiligo was widely considered a curse of the devil and thus, her uncle abandoned her at an orphanage. It was there where Michaela bore the brunt of relentless taunts, neglect, and abuse; being deemed “the devil’s child.”

At a very young age, Michaela caught in the corner of her eye a magazine at the orphanage, featuring a poised ballerina en pointe. This was the moment when Michaela was not only introduced to ballet, but rather, completely, totally, and utterly enamoured with ballet. Soon after, Michaela was adopted to a family in the US; becoming one of the nine children adopted, making it eleven children in total.

Michaela’s new parents quickly recognised her innate talent for ballet. They promptly enrolled her in ballet classes and supported her passion, embracing her ambitions. While attending the Rock School for Dance and Education in Philadelphia and the Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis School at the American Ballet Theatre, Michaela worked tirelessly to hone and refine her skills so she could overcome the multitude of stereotypes tied to conventional beauty and racial barriers in the world of ballet.

After Michaela was featured in the ballet documentary, first position, Michaela debuted professionally as a guest principal at the Joburg Ballet in South Africa. She also famously appeared on ABC’s Dancing with the Stars. At the age of 17, Michaela performed with the Dance Theatre of Harlem. A year later, she joined the Dutch National Junior Company, as a second-year member apprentice to the main company. At the age of 26, Michaela was ranked as a soloist.”

Her death at the age of 29 (10th September 2024) is still unknown to the public, but her passion for dance still lives on in the young women and men she has influence, inspired and encouraged.

Some big movers and shape-ers

The shapes and movements both Life Models and Dancers make are not too dissimilar, flowing from one shape to another; one practice in seconds, the other in minutes and sometimes hours. Both practices can draw great inspiration from the other.

1920s The Nicholas Brothers

Perhaps unusually – or apt for the time – Fayard & Harold Nicholas were born into a family of artists, with college educated musicians for parents, they were frequently taken to rehearsals and practices from a very young age. Their mother, Viola, was a classically trained pianist, and their father, Ulysses, was a drummer. They performed together in pit orchestras for Black vaudeville shows throughout the 1910s to the early 1930s, forming their own group called the Nicholas Collegians in the 1920s.

The Nicholas Brothers had begun their careers at a time when opportunities were few and stereotyped roles the norm for Black actors and entertainers. To their credit, however, the Nicholas Brothers rose above this marginalisation and, with a sense of dignity and a style all their own, earned the respect of generations of tap dancers and audiences the world over.

The crowning achievement of their work was preserved in the film Stormy Weather (1943), which had an all-Black cast. In it the brothers, suited magnificently in white tie and tails, dance on, over, and around the Cab Calloway Orchestra bandstands, dance side-by-side up a flight of stairs, leap onto a piano where they trade syncopated notes with the pianist, jump out onto the floor in full splits, dance up a divided stairway built of gigantic white stairs, meet at the top to exchange a few thrilling moves, and then leap into splits and slide down separate ramps, meeting once again on the dance floor to finish this dazzling routine with a crisp bow.

1930s Katherine Dunham

Katherine Dunham revolutionised American dance in the 1930’s by going to the roots of Black dance and rituals transforming them into significant artistic choreography that speaks to all. She was a pioneer in the use of folk and ethnic choreography and one of the founders of the anthropological dance movement. She showed the world that African American heritage is beautiful. She completed ground-breaking work on Caribbean and Brazilian dance anthropology as a new academic discipline. She is credited for bringing these Caribbean and African influences to a European-dominated dance world.

Dunham’s first school was in Chicago. In 1944 she rented Caravan Hall, Isadora Duncan’s studio in New York, and opened the K.D. school of Arts and Research. In 1945 she opened the famous Dunham School at 220 W 43rd Street in New York where such artists as Marlon Brando and James Dean took classes.

Katherine Dunham is credited for developing one of the most important pedagogues for teaching dance that is still used throughout the world. Called the “Matriarch of Black Dance,” her ground-breaking repertoire combined innovative interpretations of Caribbean dances, traditional ballet, African rituals and African American rhythms to create the Dunham Technique. Her dance troupe in venues around the world performed many of her original works which include: Batucada, L’ag’ya, Shango, Veracruzana , Nanigo, Choros, Rite de Passage, Los Indios, and many more.

1940s Pearl Primus

Pearl Primus, dancer and choreographer, was born in Trinidad. Her parents, Edward and Emily Primus, immigrated to the United States in 1921 when Pearl was still a small child.

Primus was raised in New York City, and in 1940 received her bachelor’s degree in biology and pre-medical science from Hunter College. However, her goal of working as a medical researcher was unrealised due to the racial discrimination of the time. When she went to the National Youth Association (NYA) for assistance, she was cast as a dancer in one of their plays. Primus’s promise as a dancer was recognised quickly, and she received a scholarship from the National Youth Association’s New Dance Group in 1941.

In 1948 Primus received a federal grant to study dance, and used the money to travel around Africa and the Caribbean to learn different styles of native dance, which she then brought back to the United States to perform and teach. She also choreographed dances that contained messages about racism and discrimination. One of her dances, Strange Fruit, was a protest against the lynching of Black people.

Eventually Primus formed her own dance troupe which toured the nation. She also opened a dance school in Harlem to train younger performers. In 1953 Primus returned to Trinidad to study dance there, and met her husband, Percival Borde. They married, and had one son together who also showed promise as a dancer. In 1958 at the age of 5, he made his professional debut and joined her dance troupe.

Pearl Primus continued to teach, choreograph, and perform dances that spoke of the human struggle and of the African American struggle in a world of racism. In 1978, she completed her doctoral degree in dance education at New York University’s School of Education. Also, by this point her dance school, the Pearl Primus Dance Language Institute, was well known throughout the world.

1950s Janet Collins

When Collins was just 15 years old, she auditioned for the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, and was told by the director that she could join the company only “if you paint your face and body white.” Collins turned down the job, but later went on to perform lead roles on Broadway in Cole Porter musicals.

Then in 1951, after spending a year in the corps de ballet, Collins made history as the first and only Black dancer to be promoted to “prima ballerina” status in the Metropolitan Opera, when she made her debut as the leading dancer in the production of “Aïda.” (Excerpts from Refinery29)

Ms. Collins remained active throughout the 50s touring with her own dance group throughout the United States and Canada. She later taught at various academies including San Francisco Ballet, Harkness House, Manhattanville College and SAB for an additional 2 academic years, from 1967-1969.

She passed away in 2003, but her tremendous impact in dance continues to inspire and influence today. We encourage taking a deeper dive into her remarkable life story by reading the biography, Night’s Dancer: The Life of Janet Collins, by author Yaël Tamar Lewin. The book highlights the career of this pioneering artist, drawing partly on materials donated by Ms. Collins herself. And for our younger readers, Brave Ballerina, The Story of Janet Collins, written by Michelle Meadows with illustrations by Ebony Glen, is a perfect introduction to this true trailblazer in ballet history!

(Excerpts from SAB)

1950s Raven Wilkinson

In 1955, Wilkinson became the first Black ballerina to join the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo. But when Wilkinson began touring, particularly through the racially segregated South, she worried that her race would put the company in danger. Wilkinson was encouraged by directors to wear white makeup and keep quiet about her race — or lie

and say she was Spanish. Once, in Montgomery, AL, a Klu Klux Klan member stormed the company’s tour bus looking for her. “Several big strapping male company dancers got up and moved toward him,” she told Pointe Magazine in 2014. During the same trip, KKK members interrupted performances shouting profanities at Wilkinson while she danced.

Eventually, Wilkinson voluntarily left Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo for the Dutch National Ballet. “It wasn’t me running away from dance, though I did feel a little disappointment at the limitations that were placed on my career,” she told Pointe Magazine. In 1973, she came back to New York City, where she performed with the New York City Opera until 2011.

1950s Elroy Josephz

Jamaican-born Elroy Josephz, became one of the UK’s first university lecturers in dance in 1979. He started out as a dancer in 1952, when he joined Les Ballets Nègres, the first Black dance company not only in this country, but in Europe. Founded in 1946 by Jamaican dancers Berto Pasuka and Richie Riley, the company was very much made in London. Pasuka had studied ballet at the Astafieva school in Chelsea, and became interested in fusing the taut technique of classical ballet with the momentum, spirit and accents of African-Caribbean dance. The international mix of dancers and musicians who made up the company – from Jamaica, Trinidad, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Bermuda, Germany, the UK and elsewhere – could only have come together in an imperial city such as London.

Les Ballets Nègres enjoyed huge success in its day, touring Europe as well as the UK. But after the company closed in 1953, the dancers had nowhere comparable to go, and dispersed in different directions – some into the commercial dance sector, some into theatre – one, John Lagey, became the famous 70s wrestler Johnny Kwango. Elroy Josephz worked with his own dance company for a few years, performed in musicals and acted in some early episodes of Doctor Who before becoming a by-all-accounts inspirational dance teacher in Liverpool, his Afro-jazz classes keeping the fusional spirit of Les Ballets Nègres alive.

Despite a documentary film on Les Ballets Nègres from 1986, and an exhibition at London’s Southbank Centre in 1999, the company’s story hasn’t, as Burt would say, been written into British dance history. It made a mark, but left little trace – and when I talk to some of the people who appear in the exhibition, that pattern seems a recurrent concern.

1960s Judith Jamison

Recognised as one of the most prominent figures in modern dance, Jamison made her New York debut with the American Ballet Theatre at the age of 21. Portraits in the collections of the National Portrait Gallery and the National Museum of African American History and Culture and Alvin Ailey Dance Foundation show Jamison dancing her signature role in Cry, a ballet described as “a hymn to the sufferings and triumphant endurance of generations of Black matriarchs.” The performance made Jamison an international celebrity in the world of dance. It also marked a crowning moment in her partnership with Alvin Ailey, who recruited her to his dance company in 1965. Jamison danced with Mikhail Baryshnikov in Ailey’s 1976 Pax de Duke, performed to the music of Duke Ellington, and appeared in companies around the world. In 1980 she starred with Gregory Hines in the hit Broadway musical Sophisticated Ladies.

Jamison served as the principal dancer in the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre until 1980, and she was artistic director from 1989 to 2011. “I don’t feel as though I’m standing in anyone’s shoes. I’m standing on Alvin’s shoulders,” she said.

1970s Virginia Johnson

In 1969, Johnson left college to become a founding member of the Dance Theatre of Harlem, the first all-Black ballet company created by former New York City Ballet dancer, Arthur Mitchell. This was in the midst of the Civil Rights Movement, and Johnson said that some people questioned her decision to “try to do the white man’s art form.” “Well, who is anybody aside from me to say what I should do with my life?” she said in an interview with Pittsburgh Ballet Theatre in 2017. “I’m an individual. I have a dream, I should be able to pursue that dream.” Today, Johnson is the artistic director of Dance Theatre of Harlem.

1990s Lauren Anderson

In 1990, Lauren Anderson became a principal dancer with the Houston Ballet, making her one of the first Black dancers to climb the ranks at a major ballet company. Known for her athleticism and grace on stage, Anderson was definitely the “Misty Copeland” of her time. When Copeland made her debut in Swan Lake in 2017, Anderson joined her on stage during the curtain call and gave her a huge hug that swept her off her feet — the photo went viral.

“It’s still a European art form and there are still people who think the corps de ballet needs to be like the Rockettes,” Anderson told Pointe Magazine in 2017. “But things are changing, because more and more people are beige.” Today, Anderson’s pointe shoes are on display in the National Museum of African American History & Culture in Washington, D.C.

2020s Misty Copeland

Rising star Misty Copeland makes history as the first African American Female Principal Dancer with the prestigious American Ballet Theatre. When she discovered ballet, however, Misty was living in a shabby motel room, struggling with her five siblings for a place to sleep on the floor.

A true prodigy, she was dancing en pointe within three months of taking her first dance class and performing professionally in just over a year: a feat unheard of for any classical dancer. In June 2015, Misty was promoted to principal dancer, making her the first African American woman to ever be promoted to the position in the company’s 75-year history.

(Excerpts from Mistycopeland.com)

There are so many more incredible stories of trailblazers like these few that have forged paths. Research, support, celebrate and educate!

5 Years of Drawversity

This year marks our fifth year running and you can come and draw at all three of our locations. The first class of October will be at SOHO Brighton Beach House (members only) on Wednesday 9th from 6-8pm. We will be hosting three models – Yolande, Michael and Cameron – accompanied by a live band, with the serene sounds from Scarlett Fae accompanied by live musicians. Our second class will not be themed as the class will be focused on introducing a brand-new model at our Hove studio, Fine Feather Wellness on Thursday 10th from 7-9pm. Finally, we will finish the month at our first residency, Draw Brighton – with a class of poses focused on this subject – on Saturday 26th from 2-4pm with our first ever Drawversity model, the renowned, Priss Nash.

For further information and to book your space for a class, please go to the Drawversity page.

Further Reading & Viewing.

The Guardian: How black dancers brought a new dynamism to British dance

The Guardian: Ballet star Joseph Sissens: ‘I’d be in this world of gross privilege, and then I’d go visit my brother in prison’

Decidedly Jazzy: 16 Black Artists Who Impacted Jazz Dance History

Refinery29: 7 Iconic Black Women Who Changed The Course Of Ballet History

Secrets of Solo: Jazz. A Brief cultural history and characteristics of Black dance

Jukebox Collective: Black Dance Pioneers

Wikipedia: List of African-American ballerinas

BlackPast: Dedicated to providing reliable information on the history of Black people across the globe, especially North America.

YouTube: The uncomfortable truth of being a Black ballerina

YouTube: EN POINTE: Black Dancers, Black History

YouTube: Dance Legends Misty Copeland, Carmen de Lavallade, and Raven Wilkinson Discuss Diversity in Ballet

YouTube: Misty Copeland Tells the Story of Trailblazing Ballerina Raven Wilkinson

You can also book me to model for both still and movement classes, please go to my Life Model page to enquire.